We live in a period of time where information about anything is available to anyone. That includes papers in linguistics and genetics. Just because a person can read them, doesn’t mean that he/she can fully comprehend, process and evaluate the information given. Both linguistics and genetics are advanced sciences that require special studies and great commitment, it is not just something one can pick up in no time. They are also relatively new sciences, which means that there has been a period where those two fields have been maturing and are still maturing allowing views that were later found to be obsolete. Does that ring a bell? Maybe that many things in those fields are still open to everyone’s interpretation/selection?

You’ve definitely come across many blog/forum posts regarding languages and genes. With the rise of nationalism in our times, many have attempted to relate ethnic groups with each other, based on scarce linguistic or genetic data. Sometimes we know close to nothing about the language of a population, yet a common gene from a very small sample size is enough to make dithyrambic statements about it.

Even in the academic world the eagerness of explaining the relationship between languages and genes is a fact. For example, Cavalli-Sforza et al.’s (1992: 5620) concluded that “events responsible for genetic differentiation are very likely to determine linguistic diversification as well”. This view is not shared by most historical linguists for two reasons:

Nevertheless, all the examples above do not prohibit a relation between languages and genes. Significant contributions from linguistic-genetic collaboration are possible. Territories sparsely inhabited can be settled by a large number of newcomers. Although this does not happen too often, a group of people may come to uninhabited territories and nobody else comes there after them. Such events occurred way back in human history, while their frequency was reduced after the adoption of an agricultural lifestyle which in turn lead to permanent settlement and population growth.

One thing is certain and that is the fact that both linguistics and genetics will continue to intrigue people. They are going to talk about it and spread their interpretation and understanding, even when they do not master any of these sciences.

Campbell, Lyle. "Do Languages and Genes Correlate?." Language Dynamics and Change 5.2 (2015): 202-226.

Burlak, Svetlana. "Languages, DNA, relationship and contacts." Вестник Российского государственного гуманитарного университета 5 (106) (2013).

Klein W., “Language and Genetics”, Research Perspectives of the Max Planck Society (2010)

Mallory J.P., "Indo-European Dispersals and the Eurasian Steppe", Penn Museum Silk Road Symposium, March 2011, retrieved January 5 2017

You’ve definitely come across many blog/forum posts regarding languages and genes. With the rise of nationalism in our times, many have attempted to relate ethnic groups with each other, based on scarce linguistic or genetic data. Sometimes we know close to nothing about the language of a population, yet a common gene from a very small sample size is enough to make dithyrambic statements about it.

Even in the academic world the eagerness of explaining the relationship between languages and genes is a fact. For example, Cavalli-Sforza et al.’s (1992: 5620) concluded that “events responsible for genetic differentiation are very likely to determine linguistic diversification as well”. This view is not shared by most historical linguists for two reasons:

- A person has only one set of genes, while that person (or a population) can be multilingual, representing multiple languages.

- Individuals or whole communities can abandon one language and adopt another. People cannot abandon their genes nor adopt new ones.

Nevertheless, all the examples above do not prohibit a relation between languages and genes. Significant contributions from linguistic-genetic collaboration are possible. Territories sparsely inhabited can be settled by a large number of newcomers. Although this does not happen too often, a group of people may come to uninhabited territories and nobody else comes there after them. Such events occurred way back in human history, while their frequency was reduced after the adoption of an agricultural lifestyle which in turn lead to permanent settlement and population growth.

One thing is certain and that is the fact that both linguistics and genetics will continue to intrigue people. They are going to talk about it and spread their interpretation and understanding, even when they do not master any of these sciences.

Further reading/listening

Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca, Eric Minch, and J. L. Mountain. "Coevolution of genes and languages revisited." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89.12 (1992): 5620-5624.Campbell, Lyle. "Do Languages and Genes Correlate?." Language Dynamics and Change 5.2 (2015): 202-226.

Burlak, Svetlana. "Languages, DNA, relationship and contacts." Вестник Российского государственного гуманитарного университета 5 (106) (2013).

Klein W., “Language and Genetics”, Research Perspectives of the Max Planck Society (2010)

Mallory J.P., "Indo-European Dispersals and the Eurasian Steppe", Penn Museum Silk Road Symposium, March 2011, retrieved January 5 2017

Language and genes

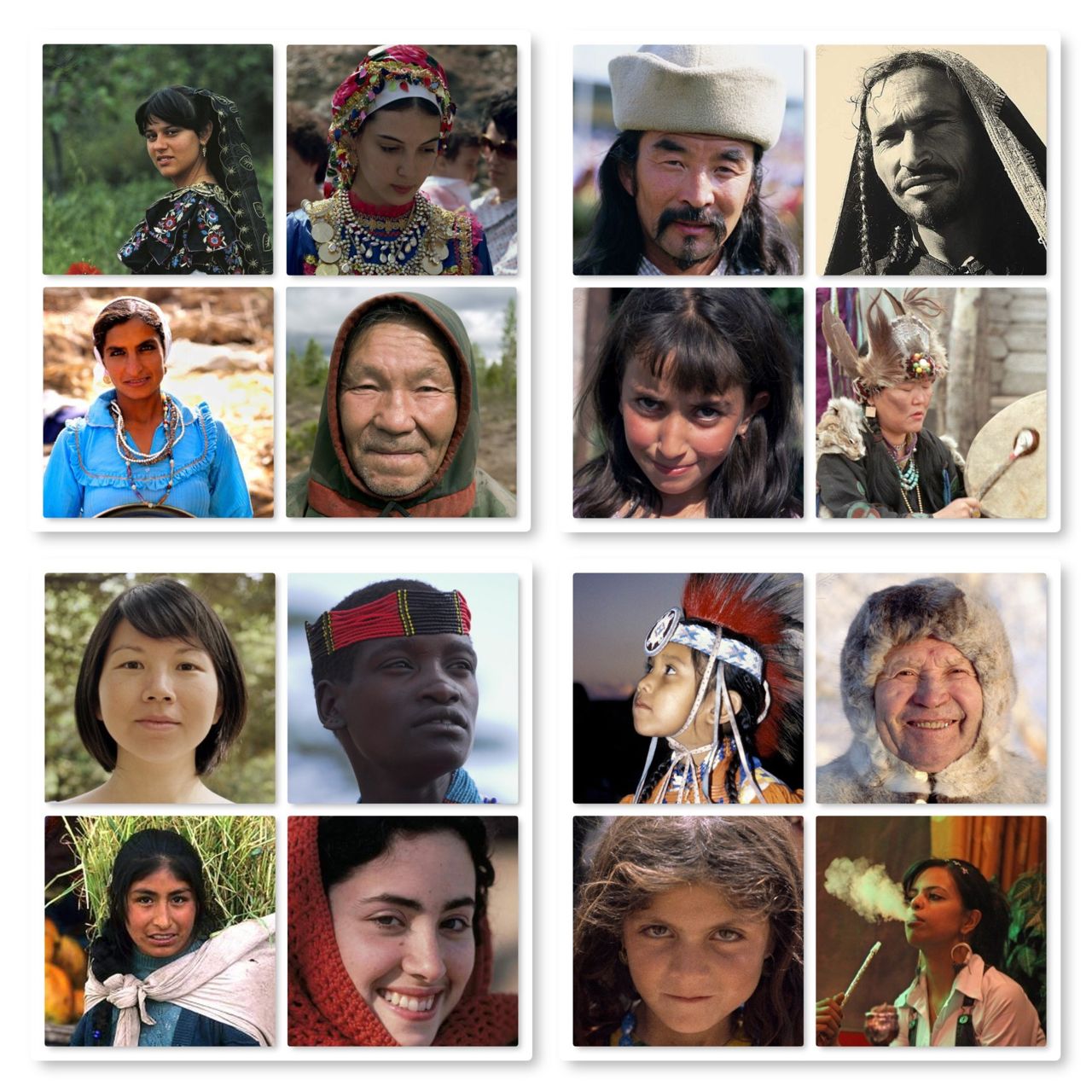

Can you guess the mother tongue of these people and the language their ancestors were speaking 80 generations back?